|

And here's the conclusion:

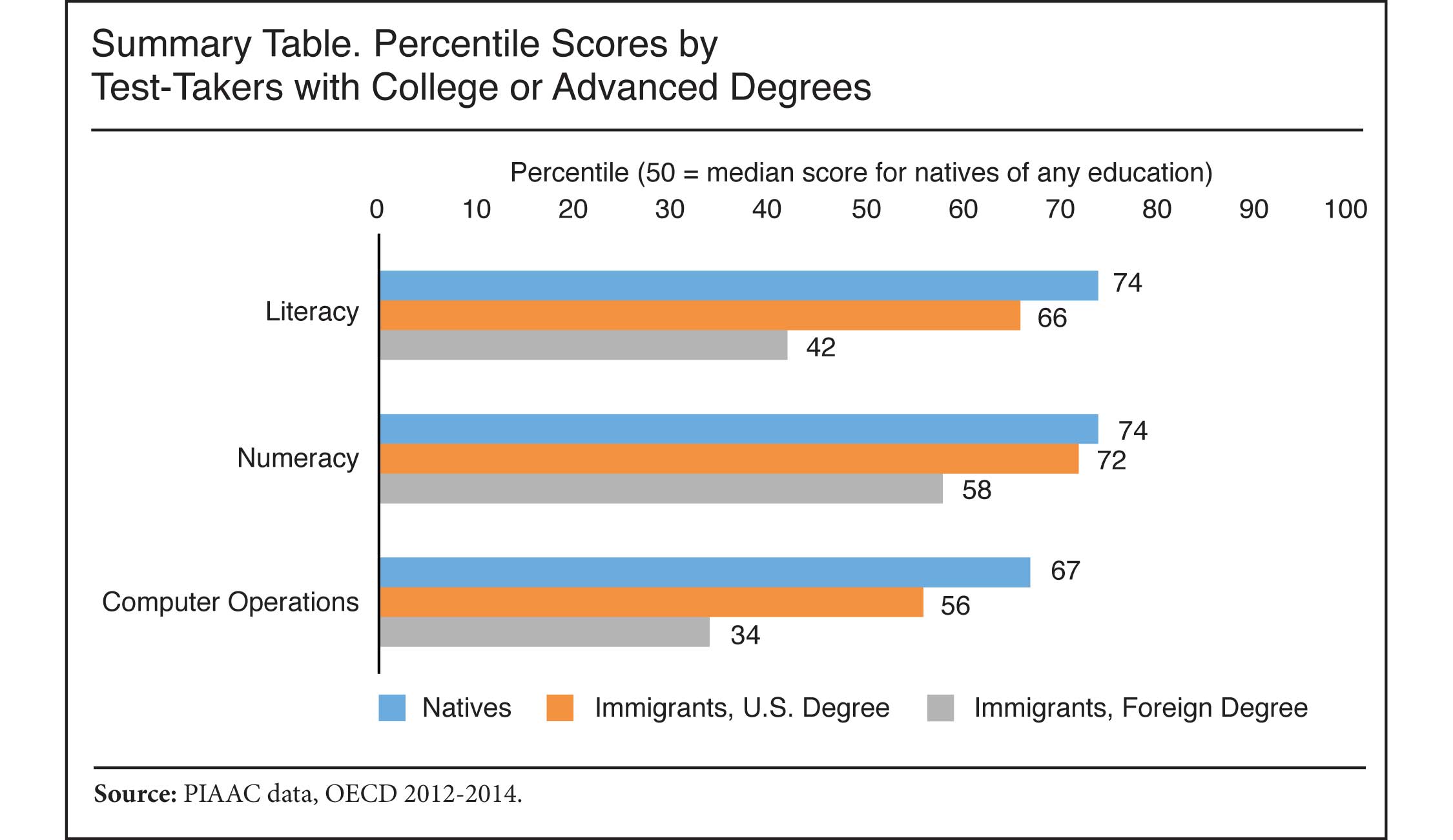

Although skilled immigration may be desirable, policy-makers must be cautious in using foreign degrees as proof of those skills. This report has shown that immigrants with foreign degrees perform substantially worse than U.S. degree holders on tests of literacy, numeracy, and computer operations. In some cases, the gaps are so large that immigrants with foreign college degrees have skills that resemble those of natives who have only a high school diploma. Although poor English clearly plays a role in the disparity — and a command of English is essential for success in most high-skill occupations in the United States — the disparity persists even among immigrants who have had at least five years to learn English after arriving.

In Congress, some proposed immigration reforms acknowledge the greater value of U.S. degrees. For example, the RAISE Act would establish a points system for high-skill immigrants that prioritizes U.S. degrees over foreign degrees. It would also go beyond educational credentials by giving extra points for English fluency, STEM specialties, and pre-arranged employment. Ultimately, policy-makers should consider making skill selection even more direct. Universities, the foreign service, and the military have been using standardized testing for decades to evaluate applicants. For example, people who want to do advanced study in important subjects such as biology, chemistry, and physics need to take the Graduate Record Exam (GRE) to demonstrate their knowledge and preparation. Perhaps Congress could integrate similar tests into a truly high-skill immigration system.Please read the whole thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment